Class 127 Derby 4-car DMUs

Power Train

Engines

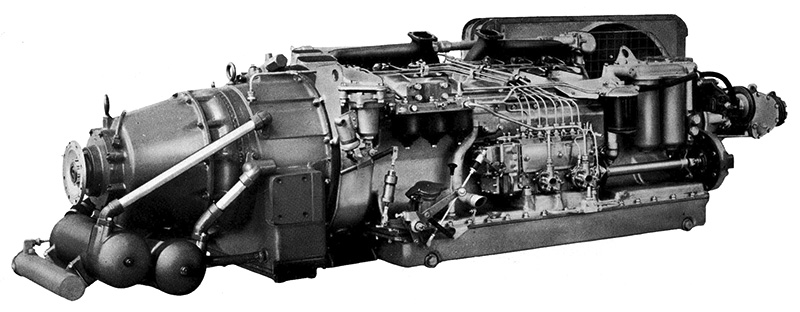

Each power car had two Rolls-Royce 823 series C8N horizontal engines, with eight cylinders of 5 1/8 inch bore and 6 inch stroke. Built at the Rolls-Royce Oil Engine Division's Sentinel Works in Shrewsbury, they incorporated a CAV hydraulic governor mounted on the fuel pump. Maximum power was 238hp at 1,880 rpm, giving a total of 952hp for a set and a power/weight ratio of 7hp per ton for the unit. Engines and torque convertors were unit in construction and slung below floor level on Metalastik flexible mountings, and each unit drove one inner axle. A Graviner automatic fire extinguishing system would shut down any affected engine and ring fire alarm bells in driving cabs and brake vans. There were four extinguishers per engine (most DMUs had one per engine). The fuel tank capacity was 95 gallons for each engine which gave a range of about 500 miles.

Transmission

The Crewe built three-stage Rolls-Royce DFR 10,000 series torque converter changed to direct drive at 46mph. For this to happen, the engine was throttled down for 4 seconds automatically and the clutch incorporated in the torque converter casing was engaged by means of a Smith-Stone electro-pneumatic control system incorporating Westinghouse ep valves and worked on voltage sensitive relays fed by the axle-driven speedometer generator.

When the train speed fell to about 39mph there was an automatic change out of direct drive back to torque convertor drive without de-throttling the engine. Under this condition the free wheel prevented shock loading of the transmission. The torque converter gave a torque ratio of 5:1 at stall and this decreased as tractive effort dropped. The absence of gear changing meant that there was no interuption of effort during acceleration to 46mph. The direct drive above that speed, up to the nominal maximum of 70mph, gave maximum efficiency.

The transmission fluid was originally fuel oil, fed by an engine driven charge pump and returned to the fuel tank after passing through a heat exchanger. It became obvious that using diesel was a fire risk, and they were converted to use their own hydraulic fluid (Shell Talona), possibly around the early '70s. A freewheel ensured the mutual independence of the engines.

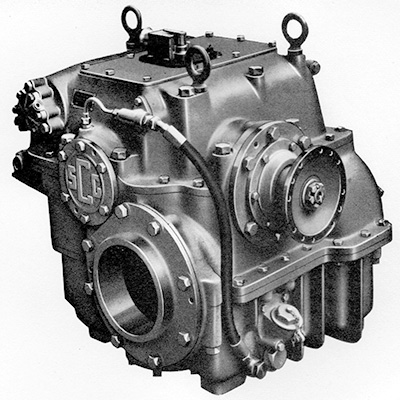

Connected to the torque converter by cardan shafts was the 2.97:1 ratio reversing SCG RF28 final drive (pictured). When the vehicle was stationary, if the selector dogs became butted to hinder engagement during the selection of a change of direction of motion, an automatic device signalled the torque converter control to cause slow rotation of the cardan shaft. Neutral gear could be selected in cases such as when the automatic coolant and lubrication fault protection shut down the individual engine. This required a local manual control to be operated by the driver. There was a carriage key switch on the solebar enabling the isolation of a single axle.

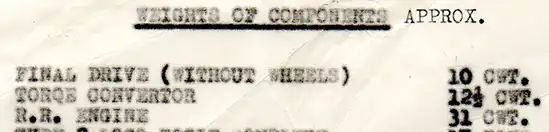

Component Weights

A 1965 Cricklewood depot letter gives the weights of the Rolls-Royce engine, torque convertor and final drive. View the full letter.

Modifications

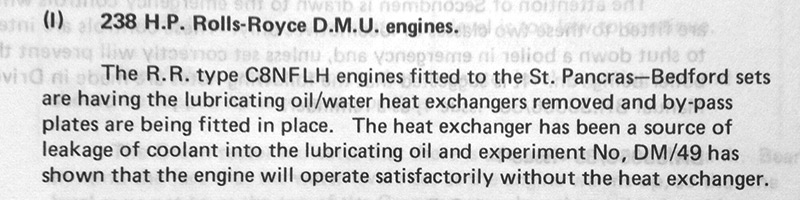

Here is details of one of the many modifications made to the class, detailed in LMR Traction Bulletin Issue 9 - January 1974.

Fire Extinguishers

Ron Stringer, a Derby C&W employee from 1963 to 1980 notes[1]: "A job I had was fitting extra fire control systems. the 127s originally had only 2 fire extinguishing systems as fitted to other railcars, the additional 2 fire systems were added as a modification. The cordite filled capillaries and perforated pipework was added around the fuel tanks. If I remember correctly when the fire detection operated two bottles operated and the second two operated when the unit had come to a stop. Fire systems were also fitted to the intermediate trailers."

References

- ⋏ Email from Ron Stringer to Stuart Mackay 3 May 2021

Summary

Background

Description

Power Train

Interiors

Works Photos

Diagrams & Design Codes

Driving Instructions

Numbering

Liveries

Operations

Accidents

Parcel Use

Images

Details about preserved Class 127s can be found here.

Also relavant is the article "Working the DMUs" by Cricklewood Driver Arno Brooks.